Heidi Guilford rode shotgun in her boyfriend's white Dodge Charger. Her stepsister and a couple friends sat in the back, with the windows rolled down for the smokers. It was a cool night in June—sweatshirt weather—an unremarkable Sunday on an island off the coast of Maine. They could have been in any small town, just about anyplace. A loud engine, blaring music, laughing shouts from the front seat to the back. And all around them:

Quiet.

Heidi knew every inch of these roads. They all did. They’d grown up on this island, Vinalhaven, fifteen miles out to sea by ferry, a rock in the ocean that the glaciers hadn’t quite smoothed over. Seven miles by five, population 1,200, give or take, and triple that when the summer people showed up.

They took a left off Heidi’s road out by State Beach and swung through town, cruising slowly through the downtown stretch, past the bar and the grocery store and the bank, then out to Old Harbor Road and over to the Basin. Most years by mid-June, there are enough tourists in town that you wouldn’t recognize everyone, but 2020 was different. This June felt more like the wintertime, when you can pretty much tell who’s driving every car on the road, often just by the headlights.

The house on Vinalhaven where Roger Feltis was killed, in June 2020.

Gregory Halpern

They were headed back toward Heidi’s place when they saw a Chevy Equinox they knew belonged to Jennie Candage racing past them. But Jennie would never drive that fast, so they figured it had to be her boyfriend, Roger Feltis. Roger was a local lobsterman, fairly new to the island, twenty-eight years old and husky—big enough that he could seem intimidating, but with a sweet, goofy smile.

They started to follow him, but he sped out of sight, so they looped back down through town and out toward the high school. That’s when Roger appeared in their rearview mirror, then pulled up alongside and told them to meet him in the school parking lot.

It was just around 9:30 p.m. Roger—wearing a T-shirt, a pair of Jennie’s old basketball shorts, and Crocs on a night when the temperature was cooler than usual, in the low fifties—got out of his car and came over to talk to his friend Isles Blackington, Heidi’s boyfriend, through the driver’s-side window. He seemed upset, bordering on frantic, going on about Dorian and Briannah Ames, a married couple who lived down on Roberts Cemetery Road, about a half mile out of town. He said Dorian had cut his brake lines and taken a hatchet to Jennie’s taillight. He said the Ameses had been harassing him, that he was sick of it, and that nothing was being done about it.

This article appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of Esquire

subscribe

Roger said he was on his way over to their house.

Everyone knew the Ameses. Not nine months earlier Dorian had been arrested for allegedly firing a gun near the gas tank of a truck a woman was sitting in, the second time he was charged with criminal threatening with a dangerous weapon, a felony. (In both cases, the felony charges were dismissed and he pleaded guilty to lesser charges.) Because of a 2015 conviction for domestic violence terrorizing, he wasn’t allowed to possess a firearm. Still, Heidi says she wasn’t scared. None of them were. All in their twenties, they’d seen plenty of fistfights—Vinalhaven is kind of a throwback that way. Worst case, they thought, someone might have to jump out of the car to break it up.

It all happened so fast. Less than twenty minutes after leaving the parking lot, Roger was bleeding to death in the back seat of Isles’s car outside the island’s medical center. The group of friends, stunned, believed they had just witnessed a homicide—one lobsterman killing another with an ax in a bloody brawl.

Downtown Vinalhaven, Maine.

Gregory Halpern

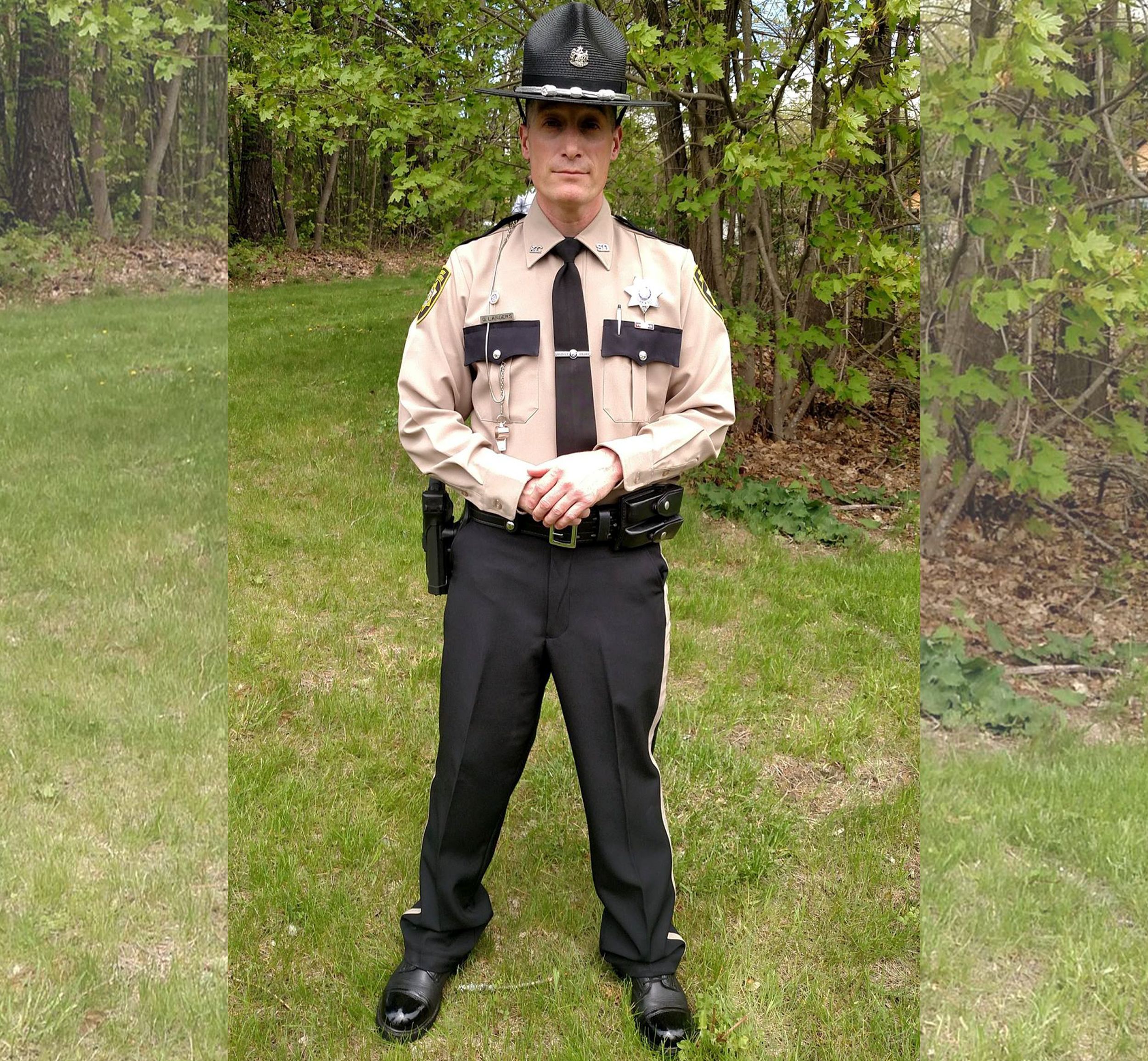

But did they? A man died—was killed, in what the state itself said was a homicide—and yet to this day, no one has been charged with a single crime related to his death. Not that there wasn’t an investigation. More law- enforcement officials than anyone had ever seen on the island descended on Vinalhaven the night Roger died. But they didn’t arrive until around 2:00 a.m.—that’s what happens when you live fifteen miles out in the ocean. No, the investigation into the violent and untimely death of Roger Feltis began in the parking lot outside the medical center, conducted by the island’s sole police officer, an amiable, forty-eight-year-old Knox County sheriff’s deputy named Dan Landers.

People called him Deputy Dan.

To get to Vinalhaven, you catch the Maine State Ferry, out of Rockland—the historic, mid-coast county seat—and arrive an hour and fifteen minutes later at a bustling port. On clear days, you can see back to the mainland, but if there’s fog—and there’s often fog—it can feel like a world unto itself, drifting out there in the Atlantic. It’s a place that’s on the way to nowhere. But even if you’ve never set foot on Vinalhaven, chances are good that you’ve seen its granite. You may have even stood on it.

Roger Feltis in an undated photo.

Gregory Halpern

The island is famous for its pink-gray rock, which for decades was carved out of quarries in massive chunks, loaded onto ships, and sent all over the country. Vinalhaven granite is in the Washington Monument and the base of the Brooklyn Bridge. It forms the entirety of the massive stone pillars surrounding the altar within Manhattan’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Today, many of those quarries are swimming holes.

On the north side—on the land hugging the Fox Island Thoroughfare, the channel separating Vinalhaven from its sister island, North Haven—you’ll find sprawling estates with private docks and tennis courts, listed for upwards of $4 million. On the south side is the village, tucked in around Carver’s Harbor, one of the busiest lobstering harbors in the state, full of fishing boats with names like Batshit Crazy, She’s All Wet, and Shit Poke.

More people live on Vinalhaven year-round than on any of Maine’s other unbridged islands, but it’s small enough that when you call the pizza place in the off-season, they probably know what you want. All the roads either dead-end or circle back to where they started.

It can feel a bit lawless out on Vinalhaven, like some sort of eastern frontier. The strength of its fishing industry means it doesn’t depend on tourists or summer people as heavily as other parts of the Maine coast do. Pirate flags wave in the harbor, and locals tell stories of “island justice,” like the one about an accused rapist who was beaten and left below the high-tide line. (He survived.)

Dorian Ames, after he was arrested for disorderly conduct for his response to the angry protests that greeted his return to Vinalhaven. The charge was eventually dropped.

KNOX COUNTY JAIL

Vinalhaven made national news when, at the beginning of the pandemic, “local vigilantes” cut down a tree to prevent some New Jersey people from leaving their property. “We’re all out on this rock together,” Heidi says. “A lot of people out here don’t want to call the police. You have a problem with someone, you go to their house. You’re going to see them tomorrow at the grocery store anyway.”

The population is sparse, but Vinalhaven has the second-highest number of arrests per capita in Knox County, which contains several other inhabited islands and part of the mainland. The community has long had an uneasy relationship with law enforcement—with outside interference of any kind, really. The town (Vinalhaven is the name of both the island and its only town) pays the county around $125,000 a year for a deputy, plus rent and expenses.

At the time of Roger’s death, Landers was that sole cop.

He seemed to have made an already tough job harder for himself. For one thing, he lived on North Haven, the tonier island across the thoroughfare. There was also the fact that some people thought he policed the way his predecessors had—pulling over little old ladies while ignoring real troublemakers. In conversations with around a dozen islanders about Landers, the adjective that came up the most often was useless.

“Dan wanted to be friends with everyone; that was his problem,” Jennie’s mom, Karen Doughty, tells me. Landers had also lost some credibility earlier in 2020 when, during a late-winter storm, after his skiff had accidentally floated off the dock, he jumped into forty-degree water in an attempt to save it, requiring several people to rescue him and catching a mild case of hypothermia.

“Like a true landlubber,” says Kyle Doughty, who is Jennie’s stepfather and was Roger’s boss. “All he showed was piss-poor judgment every time anything happened out here.”

The trouble between Roger Feltis and the Ameses started long before Roger’s death. Previous highlights included a series of Facebook posts by Briannah shortly after Roger moved to the island in the fall of 2019, calling him a pedophile using prison slang (“skinner”).

There are multiple hypotheses about the source of the enmity. One involved the fact that Roger had a daughter with a cousin of Briannah’s, and raising her as a separated couple wasn’t always easy. Jennie had known Dorian and Briannah a little bit, in the way that everyone knows everyone out there, especially if you’re the same age. For a time, Dorian had been giving tattoos out of his house on Roberts Cemetery Road, and Jennie had gotten one from him—a little lilac bush on her upper arm that she’s since had covered up. In any case, her theory was simple jealousy: Roger had battled addiction to painkillers stemming from a car accident, and she believed the Ameses were envious that he was getting his life together.

Then there was the story about the lobster boat. It was rumored that before Roger moved to the island, he and Dorian had once been up for the same job as a sternman on one of the more lucrative lobster boats, and Roger had gotten it. Getting into the lobstering industry isn’t just a matter of dropping some traps in the water and then hauling up a bunch of bugs (as lobsters are known locally). It’s a job more often inherited than chosen outright, and even then, Mainers wait years, sometimes decades, for commercial licenses. There are strict rules about the number of traps you can set. Lobstermen have territories, and setting your traps on another’s turf can lead to violent retaliation.

Jennie Candage was living with her boyfriend, Roger Feltis, when he died.

Gregory Halpern

The sternman is the second guy on the boat, charged with baiting (using dead herring, primarily) and emptying the traps. It’s a messy, smelly job, and it’s hard—days usually start before dawn. But there’s a kind of freedom in the work. In a region without many high-paying jobs, you could do a lot worse. Typically sternmen are paid a percentage of the boat’s profits, so the difference between working on a good boat and a bad boat can be huge.

But even in an industry known for being cutthroat, a previous conflict over a sternman job isn’t an entirely satisfying explanation given what ultimately happened—Roger bleeding to death from a wound that was three and a half inches deep and revealed parts of his shoulder bone.

Roger told Jennie he believed the Ameses were filing false complaints about him for everything from illegal clam-digging to selling drugs. (Landers denies the Ameses made such complaints; the Marine Patrol says it has no record, either.) According to Jennie and her family, Roger approached Landers about the Ameses multiple times in the months before his death, complaining of harassment and asking him to intervene, but nothing came of it.

At Kyle Doughty’s urging, a few days before Roger died he again went to Landers and attempted to file a formal report. Doughty texted Roger the next morning to ask how it went.

“What dan say about those cunts?” Doughty wrote.

“Never met with me said he was busy so hopefully gonna hunt him down today,” Roger wrote back. A few hours later, Roger texted Doughty to tell him the brake lines failed on his truck and he’d had to drive into a ditch to avoid hitting another vehicle. He thought someone had cut the lines.

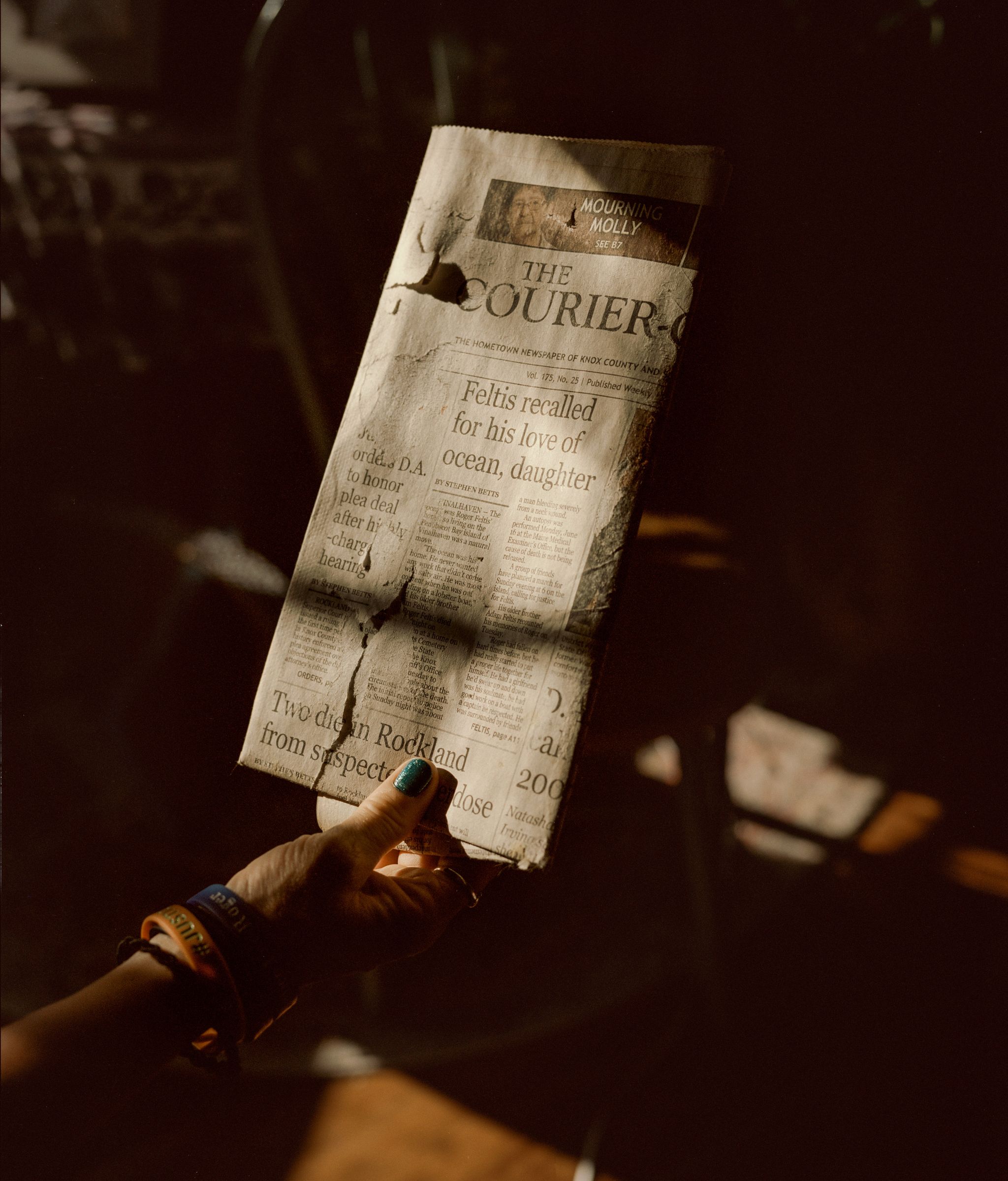

A news report of Roger’s death.

Gregory Halpern

“Wellsa wtf,” Doughty responded, using a Maine expression for “well, sir.” “Unreal man.”

Roger wrote back: “This shits gotta end today before someone gets hurt.”

Landers, for his part, says Roger did come to him about Briannah’s “skinner” Facebook posts, and about the brake lines, but that there was nothing he could do. “I can’t swab for DNA on your brake lines,” he says he told Roger. “This isn’t CSI: Miami.”

Four days later, on Sunday, June 14, Roger and Jennie went to the Sand Bar, a homey, white-clapboard-and-neon place with a ship’s wheel hanging outside and a pool table and a mudslide machine inside; everyone just calls it “the bar.” Roger and Jennie lived in an apartment upstairs.

One of Roger’s friends was there, and he started needling Roger about how the Ameses were crapping all over him. Jennie could sense Roger trying to keep his cool, not saying much at first, sipping his beer, smiling it off. But as the night went on, he kept winding up, and now she could see: Roger was pissed. Around 7:00, Jennie got up to use the bathroom. When she came back, Roger was gone.

A few minutes later, he blew back in the door of the Sand Bar and said he’d been at the Ameses. He’d kicked down their door, he said. No one was home.

They had a couple more drinks. Sometime before 9:00, Jennie carried their takeout containers upstairs to the apartment, annoyed. She had wanted to eat dinner in bed watching television with Roger. But he took off in a car with his friend to pick up another, then came back and said he was taking Jennie’s car to pay a second visit to the Ameses’. She yelled at him—she begged him—not to go.

He peeled off into the cool night.

Roger pulled into the driveway of the Ameses' place, a rental with a big front deck out on Roberts Cemetery Road, across from a gravel pit. He got out and started shouting about his brake lines. Dorian grabbed a small ax, stomped across the yard, and smashed a taillight on Jennie’s car.

Roger got back in the car and tore off, racing around until Heidi and her friends spotted him. Jennie had gone looking for a friend who she hoped might calm Roger down, and she arrived in the school parking lot right after the rest of them. “Roger began screaming at me to bring him to Briannah and Dorian’s house, to which I replied I wasn’t, but he insisted, saying if I didn’t bring him he would go no matter,” Jennie wrote in a statement submitted to Maine State Police later that summer. “So I brought him down.” Heidi and her friends followed behind. Briannah called Dan Landers via Facebook at 9:37. At 9:38, she messaged him: “WHERE THE FUCK ARE U when I need you dude.”

Jennie’s stepfather (and Roger Feltis’s boss), Kyle Doughty.

Gregory Halpern

One minute later: “DANNN THESE PEOPLE ARE HERE”

And then:

“HELLLOOOO”

“U SAID NOT TO LET DORIAN GET IN TROUBLE”

“BUT UR NOT ANSWERING”

Landers says he didn’t receive these notes, sent via Facebook Messenger, until much later.

All six witnesses to what happened next—Roger’s girlfriend, Jennie Candage, twenty-seven; Heidi Guilford, twenty-three; Heidi’s boyfriend, Isles Blackington, twenty-one; their friends Hannah Jo Moody, twenty-one, and Hayley Bryant, twenty-two; and Heidi’s stepsister, Ruby Hopkins, twenty-three—say they saw virtually the same thing: “I saw Roger get out of Jennie’s car and walk to Dorian’s front door.” “I saw Dorian come out of the house with an ax in his hand. Roger backed up and held his hands in the air and said, ‘Put the ax down and fight me like a man.’ ” “That’s when Briannah said, ‘Oh, you wanna fight like a man,’ and punched Roger in the face.” “Roger put his hands up to defend himself, and Dorian said, ‘I’m gonna kill you, Roger. I’m gonna fuckin’ kill you.’ ” “Briannah then pushed Roger against the house. She screamed, ‘Hit that bitch, Dorian, hit that bitch.’ That is when I saw Dorian swing the ax.” “Dorian reached around Briannah while swinging the ax in Roger’s direction.” “Dorian waited for the perfect opportunity to hit him with the ax.” “I could see Dorian swing the ax, and then Roger started walking down the porch steps.” “Roger stumbled down the porch stairs and headed towards Isles’s car.” “As Roger approached the vehicle, I could tell right away that something was not quite right. I could see a dark line running down between Roger’s neck and shoulder. I noticed the line start to spread as he got closer to the vehicle.”

Hayley, Ruby, and Hannah jumped out of the car to make room for Roger, who collapsed in the back seat of the Charger.

“The next thing I remember was being in the car on top of Roger, reaching into his neck and grabbing his artery so I could stop the bleeding,” Jennie’s statement reads.

Through Dorian’s court-appointed attorney, Dorian and Briannah declined to be interviewed for this story.

The Islands Community Medical Services building is a small, one-story brick structure, 1970s vintage. Landers pulled up in his police cruiser and found a large group, including Jennie, Isles, and Heidi, in one part of the parking lot and Briannah perched on the bumper of an ambulance some thirty feet away.

The investigation into the death of Roger Feltis began in the parking lot outside the medical center, conducted by the island’s sole police officer, an amiable, forty-eight-year-old Knox County sheriff’s deputy named Dan Landers.

Knox County Sheriff's Office

Landers approached Briannah, whose hand was being tended to by an EMT. “She was awake, alert, and spoke to me in a coherent manner, although she was clearly emotionally distraught,” Landers wrote. His report of the incident contained a number of errors—beginning with the date, which he listed as June 15. He called Jennie “Jeannie” throughout. “[Briannah] excitedly uttered that Roger Feltis had come to her house and that they fought and he (FELTIS) had stabbed her,” he wrote. “A group of individuals nearby said, ‘They killed him!’ To which I replied, ‘Killed who?!’ Briannah responded to that, ‘I didn’t kill him!’ Jeannie [sic] Candage (ROGER FELTIS’s girlfriend) was crying, ‘They killed him!’ ”

Landers identified Jennie’s Chevy Equinox as a RAV4 and Isles’s Dodge Charger as a Ford Mustang—though he did note, correctly, that it was “covered inside and out with blood.”

“I made contact with ISLES BLACKINGTON who was standing nearby and asked why ROGER was in his car,” Landers wrote. “ISLES said, ‘Because he was bleeding fucking to death dude.’ I asked ISLES who had injured ROGER. ISLES immediately said, ‘DORIAN.’ ”

Roughly an hour and a half after they had arrived at the medical center, Marc Candage, Jennie’s father and the island’s fire chief, who had been among the first to respond that night, told his daughter that her boyfriend was dead.

Back on the mainland, a swarm of Knox County sheriff’s deputies and detectives from the state-police major-crimes unit were preparing to board a Marine Patrol boat, most wearing suits. They would arrive around 2:00 a.m. Landers said later that he was impressed not only by their formalwear but by the fact that they were wearing cologne.

Karen and Kyle Doughty, Jennie's mom and stepfather, live in a tidy white farmhouse on East Main Street. Jennie, who was given Valium at the medical center to calm her nerves, spent the night at their house instead of returning to the apartment above the bar. She slept on the couch in her mother’s living room. Her sister, Bethany, and a friend slept next to her on an air mattress on the floor.

The next morning, Doughty had to go out on his boat—he had more than $600 in bait he needed to get in his lobster traps. Marc Candage, his wife (Jennie’s stepmother), and the girls were there at the house with Karen. They were sitting in the living room, chatting. Karen was facing the glass front door, which looks out onto the street. She recognized the dogs first: Dorian’s dogs. At first she couldn’t believe what she was seeing, but there, at the edge of her yard, was Dorian Ames. Walking his dogs down the sidewalk, as normal as could be, right in front of the house, nearly half a mile from where he lived. She had never seen him here before. She’d never seen him walking his dogs anywhere, for that matter.

She tried to get Candage’s attention without the girls realizing what was happening. Jennie was groggy from the Valium, and Karen worried that Bethany might go flying out of the house to confront him. Nobody had gotten much sleep. She pulled Candage outside and told him who’d just passed by.

Are you sure? Candage asked.

I’m positive, Karen said.

Dorian turned around and walked back past the house, slower this time. Candage and his wife ran over to the public-safety building to demand answers: Why on earth wasn’t this guy in custody?

Eight Days Later

Karen got a call at 2:05 the following Tuesday. The state police had just given a friend a heads-up: Dorian Ames was on the one-o’clock ferry. The ferry schedule practically keeps the time on the island; everybody knows that the one-o’clock gets in at 2:15.

Dorian would be on Vinalhaven in ten minutes. A small town can be a funny place. Like a bubble world, where a local event or rumor or issue or referendum bounces around, louder and louder, finally echoing so loud that you can’t not hear it, until it becomes the only thing in the world that matters, because this is your town, and your town has an equilibrium, and equilibriums are fragile. And you want to protect it.

And when that small town is on a rock fifteen miles out to sea?

Jennie’ mother, Karen Doughtry.

Gregory Halpern

Word of Dorian’s arrival spread quickly, and people began gathering at the ferry terminal and at the house on Roberts Cemetery Road. “About a hundred Vinalhaven men walked up around the corner and just stood,” Kyle Doughty says, though news reports from the day pegged the number of people outside the Ameses’ house at closer to thirty. “Everybody just standing there, keeping an eye. We’re gonna go everywhere that he goes.”

Dorian had disappeared from the island after Roger’s death—no one seemed to know for sure when, or where he went. Even back on the mainland, where Vinalhaven sometimes feels like some distant place—beautiful to visit, but somewhere you’re not entirely sure you’re welcome—people were talking about “the ax murder” and the suspect who had been spotted walking his dogs the morning after.

Dorian went to the house to collect some belongings and reappeared a little over an hour later—this time being led by police back to the ferry terminal, where the crowd had grown. He had flipped off the protesters at his house and spat at them from his car, so the police arrested him, ostensibly for disorderly conduct. But the state eventually dropped that charge, and Landers says they, in effect, arrested him largely for his own protection. “They were gonna, like, lynch him,” he says. “It was right out of an Alfred Hitchcock movie or something. The natives are restless. That’s legit what it felt like.”

One person livestreamed the scene, a video that’s still on Facebook in a private group dedicated to Roger’s memory. In it, a couple dozen people are milling around the ferry parking lot. A handful of sheriff’s deputies and Marine Patrol are there.

Dorian appears in the frame, wearing a black hooded sweatshirt and dark shorts. He walks quickly, with his hood up and his head down, surrounded by officers. His hands are free.

People in the crowd start shouting: “Murderer!” “Fucking pussy!” “Cocksucking chicken shit!” “Where the fuck are his cuffs?” The officers take him swiftly past the crowds and down to a long dock toward a Marine Patrol boat.

And then you can hear a voice, a man we can’t see, say, his voice steady but spiked with angry incredulity: “My tax money’s paying for you guys to protect him? Seriously? I beat up a pedophile, I get threatened to go in jail for a month. He fucking murders someone, you guys give him a ride to the fucking mainland? This is why the fucking police are useless. This is why we don’t call you out here, because you are fucking useless. We call you, you come out, nothing fucking happens. That is why vigilantes and Vinalhaven island justice is the way we do shit. He’ll get his. He’ll fucking get his. Don’t worry. You can’t protect him forever.”

Someone lets out a piercing scream: “JUSTICE FOR ROGER!” The entire crowd starts chanting it in unison, over and over, as the Marine Patrol pulls off the dock.

For a few weeks, Vinalhaven sat tight, everyone waiting for the arrest they were sure would come. The cops and investigators had left. Heidi and her friends who were there that night were interviewed but were surprised they’d never been asked to give formal written statements. (It was only later that summer that they wrote and sent them to Maine State Police.) The Knox County district attorney’s office had assured Jennie and her family that they were going to bring the case before a grand jury, that it was just a matter of “dotting our i’s and crossing our t’s.” Karen remembers them saying that over and over.

A tall ship etched into local stone.

Gregory Halpern

Less than a month had passed since Roger’s death. Jennie was given a date when she would testify in front of the grand jury; a person from the DA’s office asked her and her family not to tell anyone about it because nobody wanted a scene at the courthouse like the crazy one that had unfolded at the ferry terminal out on Vinalhaven—it might influence the grand jury. At the courthouse, an imposing brick building dating to the 1870s, Jennie’s testimony took about twenty minutes. She knew of only one other witness, the investigating officer from the major-crimes unit. She and her family went to eat lunch, then were called back and informed that the grand jury had come back with a decision: “No bill.”

Roger’s mother dropped her face into her hands and let out a cry. The others gasped and stared at the prosecutor on the other side of the room.

No bill?

No bill, they were told, meant that neither Dorian nor Briannah would face any charges in the death of Roger Feltis. The state maintained that Roger hadn’t been killed with an ax but rather that the wounds on his shoulders and back—one of which was nine and a half inches long, an inch and a half wide, and an inch deep, revealing parts of bone—had been caused by a fillet knife, which Briannah had used in self-defense, they said.

The state doesn’t keep track of how many grand juries come back “no bill,” but Dorian’s court-appointed attorney, Jeremy Pratt, later told the Bangor Daily News that he’s represented a thousand clients and this was the first time he’d seen this: “I always assumed the grand jury was a rubber stamp of the state, so it was great to see a grand jury make a deliberate, independent decision.”

"No one was supposed to die," Briannah says. "Nobody wanted to see him dead. . . . In that type of situation, when someone is trying to kill you, you have to defend yourself.”

She’s wearing a Red Sox jersey, and her right hand and forearm are covered in bandages. The camera is angled down at her face while she speaks; she sounds frustrated, defiant, at times even a little rueful. She talks to the camera, occasionally stopping to read and respond to the comments coming in over Facebook Live. She does her makeup throughout. Dorian paces the dim room behind her, sometimes leaning over his wife’s shoulder to speak to the camera. He smokes a cigarette and sips something from a can. You can’t make out much else in the low, gritty light. The theme song for Unsolved Mysteries, at one point, plays faintly.

“We’ve been nothing but attacked the whole entire time, and we didn’t commit one crime,” Dorian says. “Not even one.”

The video, which they filmed on the night of July 8, 2020, the same day the grand jury came back “no bill,” goes on for twenty minutes.

Briannah tells the camera she was in the shower when Roger arrived back at their house, kicked down the door, dragged her out, and cut her fingers “near off.” Later she says she texted Landers from inside the shower. “And everyone’s saying [Roger] didn’t come with a weapon?” she says, holding up her bandaged hand for the camera. “The cops didn’t want to go into detail and tell people what really fucking happened, so I’m going to. Because that’s fucking bullshit. It’s pretty bad I have to defend myself because the cops and everybody are so fucking scared of the Vinalhaven community. . . . I reached out to the police for help. I tried to get them there. They didn’t show up. That’s on them.”

“That’s a fucking lawsuit right there,” Dorian says. “I had everything lined up. I had a good fucking job. I was buying a fucking house. Taking care of and providing for my fucking family. Living the American fucking dream. And boom. Roger Feltis fucked it up in one fucking day.”

Shown outside the house where the Ameses lived, witnesses to whatever happened that night included, from left, Hayley Bryant, Hannah Jo Moody, Ruby Hopkins, Heidi Guilford, and Isles Blackington.

Gregory Halpern

Investigators found no evidence that Roger was armed when he went to their house the third time, but Briannah and Dorian say he stabbed her and that she reached for the fillet knife only after she realized her hand was bleeding. “He had a chance to leave after [he stabbed her] the first time, and he didn’t,” Dorian says, as Briannah brushes eye shadow onto her eyelids. He says Briannah grabbed the new Dexter Russell fillet knife “that had never even cut a fish” out of the kitchen sink strainer and stabbed Roger in self-defense.

“I weren’t fucking dying that night,” Briannah says as she ends the livestream. “And I ain’t gonna be anytime soon, either, so you’re all going to have to get the fuck over it. Really fucking quick. Because we didn’t do nothing wrong. Bottom fucking line. And now I’m gonna hop off here. Because I’ve said what I had to say. And I hope you all have a wonderful night. Bye, y’all.”

By the second week of July, it seemed as if every other vehicle on Vinalhaven had #justiceforroger written across its rear window.

One afternoon, Landers was parked in the lot overlooking Carver’s Harbor in his Knox County Sheriff vehicle. For hours, cars and trucks pulled in to yell at him, flip him off, piss on the pavement, and do burnouts—squealing their tires into smoky, noxious clouds—on their way out. The whole situation felt, as one longtime resident described it, “like a tinderbox.” A couple weeks later, during a vote to approve the town budget, Vinalhaven residents voted against re-upping the annual contract with the sheriff—the first time anyone could remember this happening. They were, in effect, electing to have no police presence on the island, the only item on a forty-eight-item town ballot not to be approved.

Landers was gone from the island within weeks.

One Year Later

Across the street from the sand bar—where Roger had lived upstairs—a small whiteboard sign was propped against a lobster trap. Someone had written, you are not forgotten roger!! and drawn two lobsters.

Around town, Vinalhaven seemed otherwise much the same as it always has. A new deputy arrived last winter, after long negotiations between the select board and the sheriff’s office. He patrols the island forty hours a week, driving the same downtown roads over and over, just like his predecessor. For some, though, things just feel different—the kind of different that you can’t go back from.

The house the Ameses were renting on Roberts Cemetery Road had sold for $130,000. A year to the day after the killing, a neighbor, Devin Walker, was fixing lobster traps with his sternman in a big workshop behind his house. On one wall hung a Confederate flag; on another, a Tupac Shakur poster.

Walker was asleep during the fight itself but woke up sometime later and saw someone smashing the windows of Jennie’s car. He said the only time he’d been interviewed by the police was at 2:00 in the morning on the night that it happened. “For five minutes, and that was it,” he says.

He had recently been visited by an attorney for the Feltis family, who was gathering information for a lawsuit against Maine’s attorney general. “I think the state has a lot of explaining to do before attorneys like that come out of nowhere and want to figure out what’s going on in the state of Maine,” Walker says. “I don’t blame them for wanting to come check it out. A lot of people would like to know.”

Lisa Marchese, who runs the state attorney general’s criminal division, declined to comment on the grand jury proceedings, or on the state’s investigative file. “What I can tell you—and what I’d be happy to tell you—is that there are some self- defense cases we don’t even bring to the grand jury,” she says. “That we just make the decision that this person acted in self-defense. And some people have criticized us for bringing this to the grand jury, because to them it was such a clear self- defense case.”

Dan Landers lives in a fourteenth-floor apartment with a view of the Washington Monument. He moved to the D. C. area shortly after leaving Vinalhaven—he’s on military leave from the sheriff’s office, working at the National Guard’s Joint Operations Center, advising generals, one of whom is on the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He had been in the Army National Guard for more than thirty years and volunteered for this work. He likes his new gig. The money is good, and it feels like being at “the center of the universe.” In January, he was on a teleconference call with President Biden.

“If I could kick fifty people off of Vinalhaven, it would be an idyllic paradise,” Landers says. “I mean, that’s just the reality of it.” He says he knew he hadn’t been the best cop for the island and that in retrospect he should have been “harder- handed,” particularly when it came to Roger. He calls Roger a “transient” and says that those who jumped to conclusions about his killing were “numbskulls” and “idiots.” “Frankly,” he says, “not to be offensive, they’re just not sophisticated enough to understand the reality of the facts.”

Landers served in Iraq and Afghanistan and says he used to keep a ledger to count the dead bodies he’d seen but stopped after 450. He says he’s desensitized, that he still has photos of Roger’s body on his phone, that he’s looked at them “a thousand times,” and that his stint on Vinalhaven was “worse for me personally” than any of his overseas tours, particularly by the end of it. He says that in the weeks after Roger’s death, everyone kept filming him on their cell phones, even during traffic stops. “It was actually kind of hostile. Suddenly I was like the devil for some reason,” he says. “One thing the Iraqis weren’t doing is they weren’t, like, calling my mom names on social media.”

As for the investigation, he says he was impressed by the detectives, and he had no reason to believe that they hadn’t done their due diligence. Maine has hardly any murders, after all, and the major-crimes unit prides itself on its high clearance rate. He allows that it was possible that they were in a hurry to get off the island. “I mean, maybe they were all super tired,” he says. “They could also have been like, ‘We want to get the heck out of Vinalhaven.’ I’ve been there myself.”

And yet this past summer, Landers did go back to that place—not to Vinalhaven itself, Lord no, but to North Haven, across the thoroughfare. His old home. At the Rockland ferry terminal, he walked across the gray parking lot and waited for the boat. The Vinalhaven boats are hulking white ships with hulls painted deep red and dark blue. He boarded the smaller ferry that makes the North Haven trip three times a day, the way he had countless times before. The ship blew its horn, as it always did. The thrusters churned, and slowly the boat slid away from the dock and into the Atlantic, picking up speed, past the breakwater and the lighthouses, the mansions lining the coast, past the fishing boats with the seagulls diving and swooping after them, and out toward the islands: beautiful and rough, peaceful and wild. The mainland grew smaller and smaller behind him, until after a while it was just a bumpy line along the horizon—the tidy bustle of downtown Rockland, the other towns beyond, the highway, and the cities and mountains for thousands of miles beyond that reduced to abstraction. And then, by the time the boat entered the channel that weaves through the islands, the mainland, and the rest of the world, had disappeared altogether.